Persecuted and Forgotten?

A report on Christians oppressed for their Faith 2015-17

KEY INDICATORS & FINDINGS

Horrific accounts of genocidal atrocities by Daesh during this period have emerged. A disproportionately high number of Christians fled Syria – up to half the Christian population.

STATISTICS |

PROFILE

Describing the rain of bombs which fell on Aleppo on Easter Sunday 2016, Franciscan friar Fr Ibrahim Alsabagh said: “It was more like Good Friday than Easter Sunday… People were either burying their dead or else they stayed at home out of fear.” He added: “Never, since the beginning of this terrible war, were things as bad as they are now. I have no words to describe all the suffering I see on a daily basis.” The intensification of the bombardment of Aleppo in 2016 and the increased numbers of civilian casualties made news around the world. While many media outlets focused on the government bombing of the northern held part of the city, the rebel shelling of the government-held south was just as intense – with several reports received by Aid to the Church in Need stating that the rebels had specifically targeted the Christian quarter. Aleppo, which until 2011 was home to the country’s largest Christian community of 150,000, saw an exodus of faithful, with numbers dropping to barely 35,000 by spring 2017 – a fall of more than 75 percent. Jesuit priest Fr Ziad Hilal said that those who remained there are poor and desperate for work. In many cases people are relying on charity for their food, and the Church has stepped in to help feed those left in Aleppo.

With the civil war raging it was not always clear to what degree attacks on Christians constituted targeted hatred for the minority or to what extent they were motivated by their perceived political allegiance to President Assad. However, throughout the course of the conflict Sunni jihadist militias have specifically targeted Christians – and indeed other minority groups – and religious hatred has been a key motive. The underlying religious dimension of the attacks was made plain by atrocities committed during the seizure and occupation of Christian villages and settlements. There were reports from some of the Christians who fled Homs in March 2012 that door-to-door campaigns were conducted by jihadists from rebel militias who told Christians to leave the country. The seizure of the Christian village of Sadad at the end of 2013, which saw 45 Christians killed, seems to have been a sectarian attack given its limited strategic importance. 30 bodies were found in two separate mass graves and around 1,500 villagers were used as human shields.

One of the biggest problems has been jihadists among the rebel militias. Al-Nusra Front has been responsible for many of the atrocities including Ma’aloula and Sadad – and their rebranding as the Fateh Al-Sham Front in July 2016 may in part have been to distance themselves from such events. Church reports suggested Al-Nusra were responsible for the targeted shelling of parts of Aleppo’s Christian quarter. But the complex relations between different rebel groups have meant the so-called moderate groups have – whether intentionally or not – collaborated in the attacks on Christians, eg the Free Syrian Army (FSA) fought alongside Al-Nusra to prevent Sadad being retaken at the very time when the jihadist group was committing war crimes against its Christian inhabitants.

But beyond the Islamists within the rebel opposition Daesh (ISIS) has emerged as a distinct problem, and stands accused of systematic genocide against Christians, Yazidis and other minorities in areas under its control. During the early part of the conflict it was regarded as just another rebel militia and the FSA reportedly sold on weapons to Deash. Even after the rupture between other Islamist groups Al-Nusra and Daesh over the latter’s far more extreme stance, shown in events such as the execution of British national Alan Hemming who had been doing charity work in Syria, the FSA worked alongside Daesh in a number of campaigns.

There are accounts of the group’s atrocities. Alice Assaf, whose son was killed by Daesh for refusing to change his Christian name “George” to a Muslim one, described what occurred when Daesh seized Duma, six miles north-east of Damascus. She said: “We heard that the militants grabbed six strong men working at the bakery and burned them inside the oven. After that, they caught some 250 kids and kneaded them like dough in the bakery dough machine.” This account was among incidents presented to UK parliamentarians in April 2016, shortly before the UK House of Commons voted to recognise the atrocities conducted by Daesh against religious minorities as genocide. Alice Assaf also reported that when government troops attempted to seize the city, Daesh fighters threw children as young as four from balconies to try and get them to back off. In Raqqa, Daesh closed the churches, burned Bibles and kidnapped the town’s priests. One former Daesh fighter reported that he witnessed Christians being killed on-the-spot: “They would find them and publicly execute them. I witnessed many executions.”

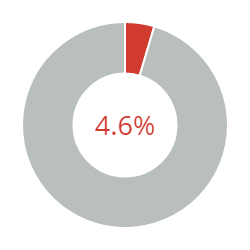

Christians – who are mostly from eastern-rite Churches, such as the Melkite, Syriac Orthodox, and Greek Orthodox Churches – are now around five percent of the population. Before the war they comprised about 10 percent, showing a disproportionately high number have fled. It is estimated that well in excess of 700,000 Christians have left Syria over the course of the conflict. Christians, who often lived in strategically important zones, fled in large numbers as these areas became caught up in the war, becoming displaced within Syria or seeking refuge outside of the country. Syriac Catholic Patriarch Ignatius Aphrem II was apprehensive about the future of Christianity in the country. He said: “I am worried that Christianity is on the way out both in Syria and Iraq as well as in Lebanon.” As a result of the civil war, half the population has fled their homes either becoming Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) or refugees. In late March 2017 the United Nations High Commission for Refugees stated that there were more than five million Syrian refugees in the region. With Syrian refugee numbers increasing by almost one million within 12 months, the crisis highlighted the repeated failure of the UN’s Geneva peace process to bring government and opposition together to find a political solution to the conflict. However, a tentative ceasefire between government and rebel forces brokered by Russia and Turkey at the end of 2016, has meant that the situation drastically improved during the latter part of the period under examination and reports of persecution have fallen as Islamist militia among the rebel groups have observed it. However, a resumption of hostilities would probably see a return to the apparent targeting of Christians. However, the problem of Daesh’s attempt to carve a caliphate out of the country remains an ongoing issue not only for Christians but for all religious minorities and all non-Sunni Muslims in areas under the extremists’ control.