ETHIOPIA

Priests face hardship on the border mountains

Every morning and afternoon, tanks drive down the only road through the mountains. They are out minesweeping. You constantly have to be on your guard, if only because of the constant presence of soldiers. The guns of Ethiopia and Eritrea are aimed at each other and ready to fire. They can be clearly seen from the backyard of the highest parish. The situation here is dubbed “no peace, no war”; always better than “war”, but without “peace”, a peaceful life is impossible.

Ethiopia and Eritrea waged a border war between 1998 and 2000, although skirmishes occurred both earlier and later, most recently in 2016. Both countries, amongst the poorest in the Horn of Africa, have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on arms. Many tens of thousands have died in this war but now there is hope for the region as Ethiopia and Eritrea have recently signed a peace agreement.

Relations between Ethiopia and Eritrea have been strained since the times of the latter’s struggle for independence – that is, from 1961 – finally proclaimed in 1993. And yet, Ethiopians and Eritreans are nations with a common history, and religion. “Many members of our families remain on the other side of the border. We have not seen each other for a dozen and more years”, observes Tesfasellassie Medhin, Bishop of the Eparchy of Adigrad, who was born here.

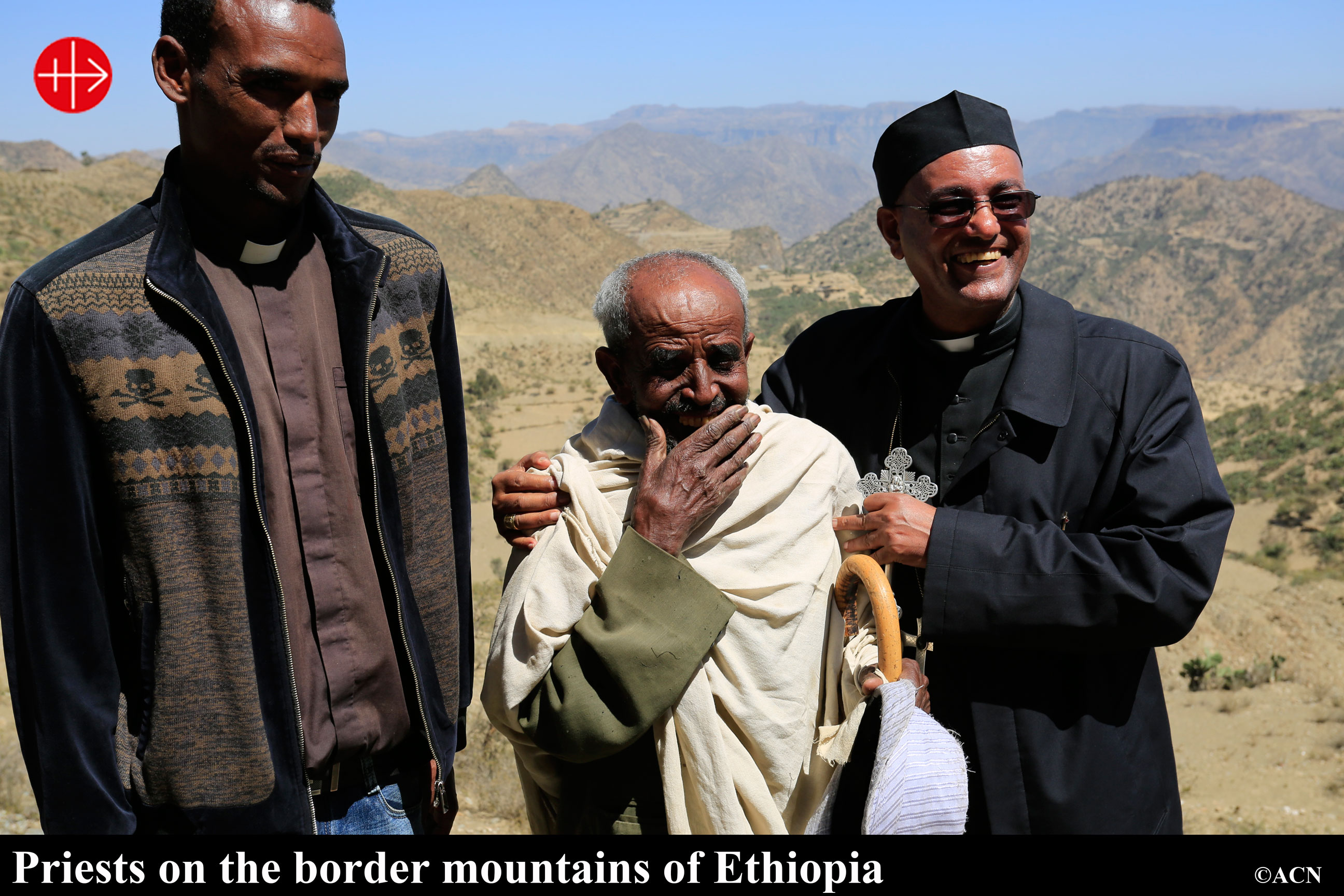

In past years this area was celebrated for its prolific number of vocations. During the war, many local priests and sisters decided to stay with the people. Some of them were held captive for up to two years – outside to begin with – like in the case of old Fr. Hagos Debesay of the Catholic Ethiopian monastery at Alitena. Seventy-five per cent of churches in these border areas were destroyed. “The walls were half torn down so that soldiers could hide behind them. Inside we found ammunition, cigarette butts, condoms”, explained Bishop Tesfasellassie, as he showed us ammunition shells still to be found around the church at Hallalise, that he had just picked from the ground. The local young parish priest, ordained not a year ago, points to the church walls. “They were almost completely demolished. We have managed to rebuild them thanks to the help of organizations like Aid to the Church in Need, but for example, we still lack benches. People pray sitting at old school desks”, further clarifies Fr. Team Fitwi, whilst he asks for more help. People who live here continue to feel the effects of the war and barely make ends meet. This area often experiences droughts. People mainly breed goats and pick honey from the mountain bees. The soil is sandy and rocky. Without rain, harvests are meagre and people and animals go hungry.

“These challenges encourage young people to abandon school and emigrate; flee to wherever they can”, explains Fr. Hagos Debesay with sadness, as he tries to figure out how to stop them. In his opinion, the answer lies in access to good quality education and work, as well as priests making young people aware of the risks associated with emigration; a continuous challenge faced by young priests working in the area, who themselves suffer both from poverty and loneliness. Solar panel installations in distant parishes are one way of overcoming these concerns. Electricity powers satellite dishes and computers, which give priests better access to the outside world, with each other, as well as the Church at large; it’s messages and teaching. This is not only about access to the latest technologies, but something that keeps priests up-to-date, and facilitates their contact with young people. Such contacts are a long-standing tradition here. The small village of Alitena boasts one of the first modern schools in Ethiopia and one of the oldest libraries with books in several languages.

Though many years have passed, travelling on foot continues to remain the norm. Transport presents the young priests from five local parishes with yet another challenge. Fr. Team Fitwi says that getting to the centre of the eparchy in Adigrad includes a three-hour walk down the mountain to catch a bus. The return journey is even worse. A car donated to the diocese by the pontifical foundation Aid to the Church in Need meets the more serious transport needs, whereas donkeys help with the regular daily ones, such as visiting patients. They are part of the so-called “donkey project”, also founded by ACN. Some villages are 8-10 kilometres distance. Donkeys carry the wine, hosts and all the other necessities to celebrate the Eucharist. Regardless of the war, drought, migration, priests do not abandon the people living here. However, they need help to remain, to serve and help the people sustain their faith.